If your classroom in any way resembles mine, the first mention of “Poetry” often sparks nearly unanimous cries of protest. Suddenly I feel like Antony fighting for my life, defending poetry like it’s Caesar’s corpse.

But I don’t want to bury poetry behind SAT prep, Common Assessments and grammar rules. I want to praise poetry. I want to reveal to students the art that lies in artistic expression. That they can expect, nay, DEMAND, I higher quality of art than we often must endure…the kind Bo Burnham satirizes in “Repeat Stuff.”

And, like anything worthwhile, the complexities require scaffolding to learn. Antony didn’t win over the crowd immediately. I won’t win over students immediately. (I definitely won’t if I push too hard too soon.) So I use a process.

I like to begin by talking about golf. I’m not a good golfer. In fact, I once wrote a song called “Double Bogey’s Par for Me.” However, my “Patented Poetry Perusal Process” fits the golf metaphor.

I ask my students, “Who has played golf…even mini-golf?” Of course, most have. “How many holes-in-one do you get?” And, of course, hardly anyone.

“So let me get this straight, you hardly ever get a hole in one? Why not? It’s too hard? Then why do people play?” And we talk about golf really being about a multiple step process of overcoming obstacles to get the ball in the hole.

Exactly. Just like poetry. People struggle with complex poems because they expect to get hole-in-ones on par four texts.

Then I draw this picture on the board:

On a typical par four hole we expect to achieve our goal on the fourth shot. For our first shot, the tee shot, we just want to move ourselves in the general direction of the flag. It doesn’t matter if we’re a few feet left, right, closer or farther away. We just hope to be in play somewhere in the fairway. In poetry, we want to do the same.

First, we just read the poem and garner some first impressions. I tell students to see if they can answer these questions in general and broad terms. “Be like a cave man or woman,” I say. Think “Good?! Or Bad?!” And feel free to grunt.

- What might the title mean? Does it establish some sort of context?

- What’s the poem generally about? The ocean? War? A Wheelbarrow?

- Does the imagery paint a happy picture or sad? Bright or dark?

- Is it in first person so that the speaker might represent a character

- Is it regular and structured or irregular and seemingly random?

- What words do I not know that I need to look up?

If we can answer these questions at all, I’d say we’re moving in the right direction. Consider ourselves in play in the fairway.

In golf, we want to use the next two shots to get onto the green. While, in golf, players must take one shot at a time, poetry analyzers can combine the next two steps, or take them one at a time. Either way, we need to identify the poetic devices and their effects while deciphering the meaning of each line.

By analyzing the effects of the poetic devices we answer questions four and five in more detail. We should look for the use of figurative language, sound devices, rhythm, and possibly irony. This process should also refine our sense of tone. In addition, this second or third reading should also clarify our understanding and interpretation of each line.

Now that we are on the green, precision becomes important. All of our previous shots have gotten us close to our goal, now our job is to place the ball in a four-inch window. In poetry, we want to establish a theme statement. What does the poet say to the world through this poem?

Using this process with students empowers them to take their time. I emphasize tho them that they are NOT STUPID if it takes them three or four readings to figure out what’s going on. Like golf, it means that it was a challenging hole and the poet is addressing a complex subject.

Once I’ve established the process, I move on to specific poetic devices.

Teaching Poetic Devices

I introduce many poetic devices using songs. As a musician, I can bring in my guitar and sing songs that illustrate the various devices. I want to do as much as I can to capture interest and my mediocre performances seem to be just enough to engage students.

I introduce the concept by listing terms and definitions on the board and explain the concepts. Then I play the song. Sometimes we will discuss the song as a class and sometimes I will put students in groups and have them analyze the poetic device, then discuss the song as a class. For homework, I ask students to find the poetic device that we covered that day in a poem or song on their own and write a short analysis explaining its effect on the overall work.

Teaching Figurative Language: Similes/Metaphors/Personification

As a high school teacher, I find that most of my students have a basic understanding of similes metaphors and personification. I find that I can move them into more sophisticated concepts like extended metaphors, metonymy, and synecdoche. I also add allusion into this lesson simple because the song that I use to teach figurative language contains an allusion.

I love using John Hiatt’s “Through Your Hands” to teach metaphor, and, if you want to get even more sophisticated, metonymy. I also reinforce the poetry process. I draw the golf image on the board and guide students through that path as we examine how figurative devices shape the meaning of the song.

In addition, the reference to the “burning bush” also provides an opportunity to talk about the power of allusion.

After “Through Your Hands” I use Sting’s “Fortress Around Your Heart” to teach extended metaphor. First, though, I introduce the concept of extended metaphor by drawing (badly) a rose on the board, an equal sign, then the word love. I explain that an extended metaphor works by establishing a broad comparison, then breaking down the comparison into parts. (“Okay, if love is a rose, what do the roots represent? The flower? The thorns?”)

Then I give students a chart play the song. I ask them to place the references from the song in the left-hand column and list possible interpretations in the right-hand column. I list the first few, the “fortress,” “walled city,” and “cries of truce” for them to get them started.

As always, I model the poetry process. As a class, we talk through the first read-through questions. In addition, I reinforce figurative language learning by asking, “You can’t literally put a fortress around your heart, can you? No? Then it’s probably a metaphor. What could it mean?”

After we’ve created momentum by establishing that the “fortress” most likely means an emotional barrier, I direct students to work in groups and interpret as many possible metaphors in the song and record them on their chart.

Afterwards, as a full class we discuss that the speaker most likely emotionally injured the character to whom he speaks, causing her to build a fortress. Students share their interpretations of the various potential metaphors.

They particularly like the idea that the speaker can’t “fill” the emotional damage of the “chasm” but hopes to “build a bridge” to overcome it. I love the artistry of the spin at the end. In the subtle line, “this prison has now become your home,” Sting takes the image of a fortress, designed to protect by keeping people out, and flips it, making it a prison that traps by keeping people in.

Teaching Sound Devices: Rhyme, Alliteration, Onomatopoeia

Many songs work to illustrate these concepts, but I really like “Last Goodbye,” by Kenny Wayne Shepherd. Not only does it contain several sound devices, but it also provides opportunities to review figurative language.

Like the previous lessons, I begin by defining and providing examples of exact, approximate, internal and external rhymes and rhyme schemes. I also define alliteration, assonance, and onomatopoeia.

After I play the song, I ask students to complete the rhyme scheme and identify as many of the terms that we defined as possible. (Not a lot of onomatopoeia in this song, but everything else!)

Once again, we review the poetry process by answering our initial read-through questions, discuss the effect of the sound devices, review the figurative language like “time was just a fist of change tossed in the water just in case” (I love that line!) and “door closes another one opens.” Finally, I have them craft a theme statement.

Teaching Rhythm/Meter

Teaching meter presents significant challenges. It reminds me of the first “band” I tried to form with my two cousins. Dan, a guitar player, has a great ear. He can pick up song relatively quickly. I can play guitar and sing (or, at least, remember the words) so we needed Dan’s brother, Mark to play drums. We set him up on the kit and showed him the basic rhythmic pattern. As long as we stomped out the pattern with him, he could stay on beat. As soon as we began playing and singing, however, the drums started to sound like drunk carpenters (Tradesmen, not the band!)

Similarly, in my experience with students I have found that people either have rhythm or they don’t. It’s a difficult concept to teach. So I work to get all students to know that meter exists and that it is often mostly either regular or irregular. Regular rhythms tend to move faster and feel brighter while irregular rhythms tend to feel slower and darker.

I introduce the concept by writing several student names of the board, which usually gets their attention. Then I ask them, “When I say these names, which sylABle should I place the emPHAsis?” After they’ve looked at me quizzically and I’ve repeated the line several times, students laugh and begin to understand my point. Then we scan their names by placing accent and unaccented marks over the syllables of their names.

“Okay, on your feet!”

I direct students to stand in a circle and then form a conga line to follow me around the room. “March in this rhythm,” I say. “Left RIGHT, left RIGHT, left RIGHT. Repeat after me: I DO not LIKE green EGGS and HAM. I DO not LIKE them SAM I AM.”

“Left RIGHT, left RIGHT, left RIGHT….”

“But SOFT what LIGHT through YONder WINdow BREAKS / It IS the EAST and JULiet IS the SUN. / ArISE fair SUN and KILL the ENVious MOON who’s SICK and PALE and PALE with GRIEF…”

I then invite students to sit down and I write out Romeo’s line on the board and divide it into syllables. “Okay, which words or syllables receive the emPAHSis? After we’ve placed the accent marks, I ask, “After how many syllables does the pattern repeat?”

“Two!”

“Exactly.” Then I draw brackets over every two syllables. “These are called ‘feet,’ like measures in music. This particular foot, with the pattern of an unnaccented syllable followed by an accented one is called an Iamb. “How many feet in this line?”

“Five!”

“What’s the prefix that means five?”

“Pent!”

“Absolutely, you guys are super geniuses. And here we are addressing math standards in English class. Be sure to DEMAND that you meet ELA standards in math class. Since these lines are composed of five iambic feet, this particular construct is called iambic pentameter. Would you consider it regular or irregular?”

“Regular!”

“Exactly. It will tend to go faster and more smoothly.”Then I add the nursery rhyme line “Hickory Dickory Dock, the mouse ran up the clock.” (This is a great one since it begins in dactyl feet and ends in iambs.)

I move away from music to teach rhythm because the beat of the music often supersedes and obscures the rhythm of the language. I find “Woman Work,” by Maya Angelou, to the the BEST poem to illustrate not only the concept of regular and irregular rhythm but also how the meter underscores the meaning of the poem.

I usually have students complete this task on their own, then we discuss it as a class. I ultimately want students to understand that the rhythms at the beginning are repetitive and fast, like her chores, while the slower rhythms at the end underscore the break and rest that the poet desires.

Teaching Irony

I teach the three types of irony: verbal, situational and dramatic. I explain that verbal irony is saying one thing but meaning the opposite. Like when my lovely bride says, “nice hat.” I point out that all sarcasm, with intent to criticize, uses verbal irony, but not all verbal irony, with intent to amuse, is sarcasm.

I find the trick to teaching verbal irony is to ask students, “how do you know, without paying attention to the tone of their voice, if someone is being sarcastic?” After discussing several scenarios, one of them usually involving my hat, we come to the conclusion that when there’s little possibility that the statement can be true, then verbal irony is likely.

I don’t always dedicate a song to illustrate verbal irony but when I do I use Annie Lennox’s “I Need You.”

I need you to pin me down

For one frozen moment

I need you to pin me down

So I can live in torment

I need you to really feel

The twist of my back breaking

I need someone to listen to

The ecstasy I’m faking

I need you

Since it’s highly unlikely anyone would “need” these things, it’s more likely that the narrator is using verbal irony to criticize.

I ask students what effect might dramatic irony, when the reader or audience knows something that the characters do not, have? I point out that in horror movies, when we know that the ax murderer is hiding in the closet but the protagonist does not, creates suspense. In the movie Mrs Doubtfire, however, (believe it or not, most students have seen it) it creates comedy.

The complexity of true Situational Irony challenges many students. I define it as “a discrepancy between expectations and reality in an appropriate way.” For example, the fire station burning down is ironic. We EXPECT that the fire station has the means to put out the fire. In REALITY, however, it burns down. It is APPROPRIATE because fire destroyed it. If aliens came and nuked the fire station, it wouldn’t be ironic. Similarly, if a famous gunslinger in the West shoots himself in the foot and dies, that’s ironic. We EXPECT that he knows how to safely handle a pistol. The REALITY that he dies APPROPRIATELY from a self-inflicted gunshot wound is ironic. A rabid elephant running him over wouldn’t be ironic. Just weird.

My favorite songs to illustrate situational irony are “Cat’s in the Cradle” (G rated) and “Taxi” (PG-13) by Harry Chapin. In “Cat’s in the Cradle” the narrator hears his son claim that he wants to grow up to be like his dad, busy and “important.” The son does turn out to be like his dad, busy and “important,” but also like his dad: too busy for family.

“Taxi,” beautifully structured, contains balanced examples of irony. The narrator, a taxi driver, picks up a woman as a fare dressed in a gown on a rainy Friday night. He soon realizes that she is an old romantic interest. They split up, however, because she wanted to be an actress and he wanted to “learn to fly.” Chapin reveals the irony at the end when he says:

And now she’s acting happy

Inside her handsome home

And me I’m flying in my taxi

Taking tips and getting stoned

Both of them express a discrepancy between expectations and reality in an appropriate way.

Re-teaching and Reinforcement

After covering each concept one lesson at a time I like to spend a class covering two or three songs/poems as a review. Students can practice identifying and analyzing the effect of many of these devices in one text.

I love playing the Police’s “Wrapped Around Your Finger.” Not only does it sound haunting on an acoustic guitar but it also presents sophisticated rhymes (apprentice / Charybdis), allusion, and metaphor/symbol. The narrator, a “young apprentice” initially infatuated with an older married woman ultimately turns her “face to alabaster” when she realizes that her “servant is [her] master.”

In addition, now that students have developed skills, I begin introducing more complex and more traditional poems. When I believe that students are ready I give them a practice exam, then the summative assessment.

Strategies for Teaching Shakespeare Sonnets

Since students have studied poetic devices, I begin the sonnet lesson by simply handing one out. I remind them to use the “Patented Poetry Perusal Process and answer the initial read-through questions. In addition, since students know how to complete a rhyme scheme I have them do that. And I ask them to scan the meter.

Sonnet Structure

After we discuss these responses, I explain the sonnet structure. I explain that sonnets, 14 line poems, can be broken into three quatrains and a couplet. The first quatrain introduces a problem and the second quatrain expounds or develops it further. The “turn” comes at line nine where Shakespeare introduces some sort of shift for the third quatrain. Finally, the couplet arrives at the solution to the problem established in the first quatrain.

Sonnet Puzzles

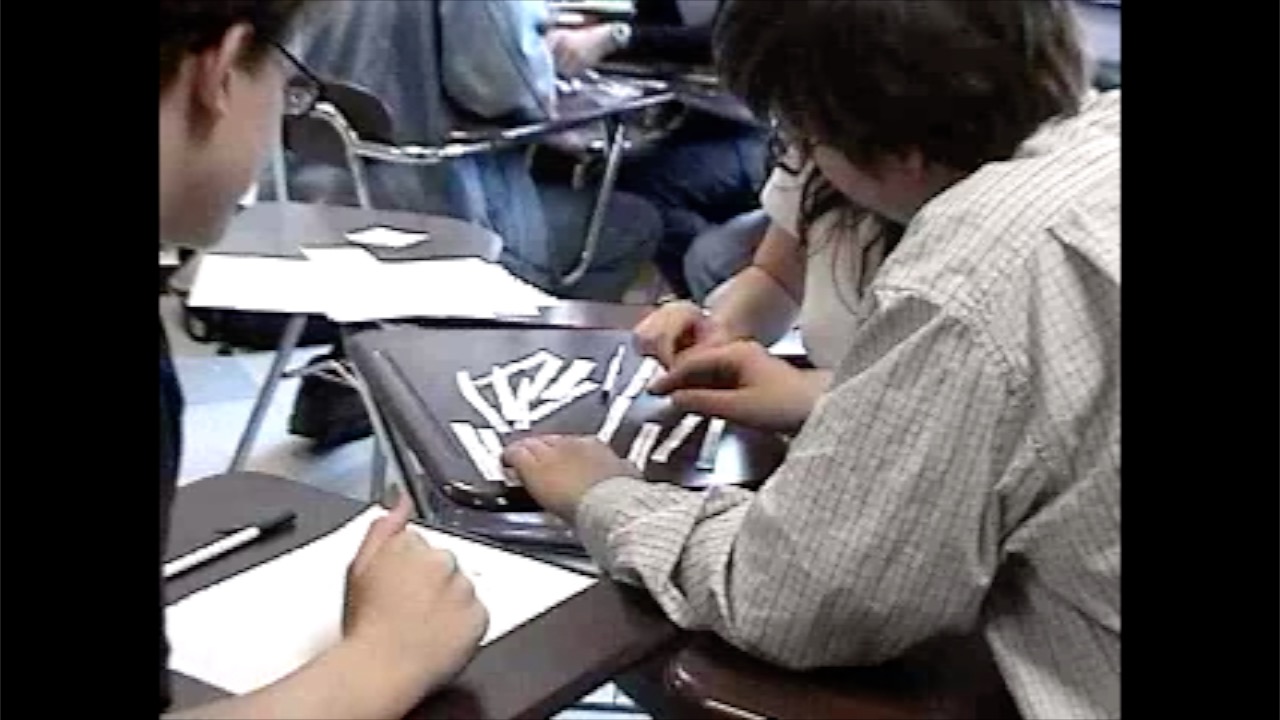

After putting students into groups of three or four, I give each group an envelope containing two sonnets. I have cut one of them into four parts: three quatrains and the couplet. The other I have cut into individual lines. Since it’s easier, I have them assemble the first puzzle first. They put the quatrains in order then add the couplet at the end. Then they tackle the second sonnet. Based on the rhyme scheme, punctuation, and meaning, they put the lines in order.

Acting Sonnets

To perform sonnets, I put students into larger groups of six to eight. They work to create a dramatic performance of their sonnet similar to the “15-Minute Play” or “Puppeteer” activity.

I break them into groups, give each group a different sonnet, the directions, and rubric. The preparation process usually takes about 45 minutes, and the performances take about 20 minutes.

Conclusion

Many students may initially express an aversion to poetry. As with most aversions, they are often grounded in fear and ignorance. By appropriately scaffolding skills and knowledge and using music to make concepts more relatable, however, I have found teaching poetry a pleasant experience!

One thought on “Teaching Poetry and Shakespearean Sonnets”