Hesitant, inexperienced, and nervous student actors often rehearse and perform with all the urgency of a snail creeping unwillingly to school. They find it difficult to understand the importance of energy without concrete instruction. Thus, giving them an anchor of various energy levels often help elucidate the subject for them.

Here is the script I use for this activity. I model each level by doing the activity with the students.

Okay, this activity is called the Seven Levels of Energy.

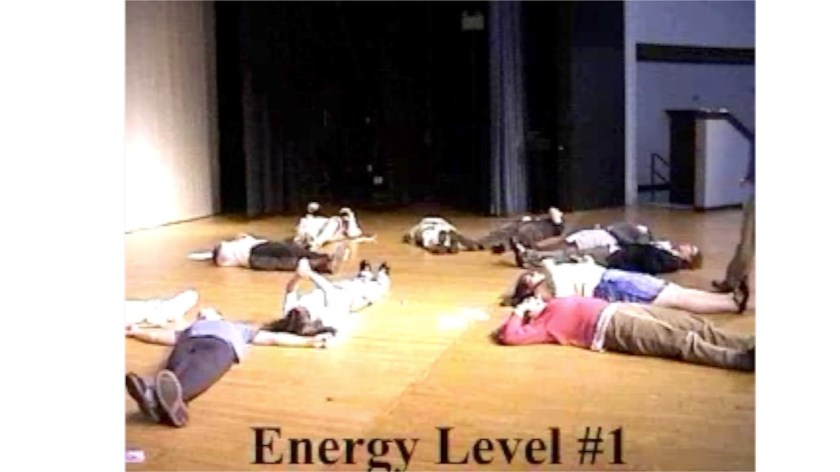

Energy Level #1

So, everyone lie down on the floor. Yes…on the floor. On your backs. Eyes closed. This is energy level number one. Imagine that gravity, an overwhelming force, pushes you into the floor. You are like a pool of liquid. You are so tired that you can barely lift your fingers. Go ahead, struggle to lift a finger. It’s Monday morning and you struggle to get out of bed at energy level number one.

Energy Level #2

Fortunately, or unfortunately, depending on how you look at it, we can’t stay at energy level number one. We have things to do. So, at energy level number two, which takes all of your effort and concentration, struggle to your feet. That’s right, do that now…struggle to your feet where you can barely stand because it feels like you have a thousand pounds on your back. You even stagger a bit trying to maintain your balance. Nope, you can’t talk at energy level number two, you can barely stand. Feel that weight on your back. Okay, good.

Energy Level #3

Well, we can’t stay at energy level number two, either, so let’s go find the coffee machine. At energy level number three, if we concentrate really hard, we can move from point A to point B. We may sway a bit, side to side because we’ve still got that heavy weight on our back. Nope, still can’t talk at energy level number 3, it takes all our concentration to get to one spot. Then we have to pause, rest then get to the next spot.

Energy Level #4

Now that we’ve had our coffee, we can move onto energy level number four. This is normal everyday walking around with no particular purpose. Oh, there’s people in this world. Yes, now we can talk to them. “Hey, how’s it going? Good. You?” Yup, just walking around with no particular purpose, no urgency. Not like you guys, of course, but perhaps some of my less motivated students…. Just walking around normally. Ho-hum. The thing is, with energy level number four, nothing gets done. There are no stakes, nothing matter, no one cares. Until we get to energy level number five.

Energy Level #5

Okay, now we’ve got purpose! We have goals to accomplish! I need to move this chair over here. I need to carry this backpack over there. Very Important! This needs to be done and done correctly or there will be consequences…significant consequences. I need to come over here and tell Jack that our performance today is essential to our success! Very important! Move with purpose. Move with urgency. Pick up the pace. I have clear objectives, clear goals. I’m motivated.

Energy Level #6

When we get to energy level six, we’re late! We’ve got to run! It’s critical! Lives are at stake! Our future! Run, run, run! This has to be done NOW!! The essay is due in 15 minutes! I need to score the winning touchdown! Go, go, go! Something really bad is going to happen if we don’t get this done! High stakes! We must not fail!

Energy Level #7

When we get all worked up, we sometimes move to energy level number seven where all we can do is scream: “AHHHHHHHHRGGGGHHHHHH!” and collapse to the floor. Back to energy level number one. We’re exhausted again and feel heavy. Kind of feels like most days of my life…

Debriefing

After completing the activity, I gather students in a circle to talk about it. I always ask, in theater, which energy level should we avoid like the plague? Inevitably they say, “Number one!” to which I reply, “My friend, Mark, once played Julius Ceasar. After they stabbed him he had to lie on stage for 15 minutes of Mark Antony’s speech. He was in three shows and was tired. I often had to kick him so he would stop snoring. That’s pretty much energy level number one”

“Okay, energy level number two.”

“Imagine you are wounded, or really old. I’ll bet you would walk like that…hunched over, feeling like you had a heavy weight on your back.”

“Okay, four! Yeah, energy level number four, avoid that.”

Exactly. Energy level number four doesn’t “read.” It communicates nothing. It’s emotionless. One, two and three can show several different emotional states. Six and seven, definitely. But four? Boring. Uninvolved. Purposeless.

I suggest focusing on energy level number five. Make sure your character work to accomplish something. Know what they want and that getting it is important to them. If your characters don’t care, the audience won’t care and they’ll be bored with your scene.

Think of theater like the Arnold Schwarzenegger movie Kindergarten Cop. Has anyone seen it? No? I know, I’m getting too old. Anyway, in this movie, Arnold plays a police officer. He’s used to getting what he wants, justice, by beating up bad guys. However, when he takes an undercover job as a kindergarten teacher, he can’t beat up little kids, so has to learn to use LANGUAGE to achieve his goals. That’s what theater is all about. Think about how your character uses words to accomplish goals.

Bonus Strategies

Although the Seven Levels of Energy activity works well to communicate the theory, sometimes students need some additional practice to put the concept into practice. If I see a group hovering around energy level number four, I usually give them two additional challenges.

Four Corners

I place each of the scene members in the four corners of the performing space…the farther apart, the better. If we rehearse in the auditorium, I tell them to stand way out in the corners of the seats. “Okay,” I say. “Stay in character and project your lines across the space to your scene partners.” While this challenge works well for “soft talkers” as well, it helps to increase the energy with which they speak.

Speed-through

Another strategy I use to increase energy levels is the speed-through. I tell students to literally RUN through the scene, speaking as quickly as possible without losing any of the sounds of their words. Imagine that you are racing another group performing the same scene. If you drop any words, you’d have to restart, so maintain line integrity, but GO FAST! This often creates the urgency necessary to transform a lackluster energy level to a more dynamic one.

Fun Fact

I was presenting this activity at a conference in Denver one year and during energy level number six someone moved my presentation notes. I never found them. Luckily I had my presentation pretty well anchored in my head so we were able to press on without any problems. It was a fun group and well worth losing notes!

Acting Shakespeare can understandably intimidate students and inexperienced actors. This reluctance often translates into dull scenes that do little to combat the notion that Shakespeare plays are lively and dynamic. However, these teaching strategies will help reticent students understand the appropriate energy level necessary for entertaining scenes!