When I was a kid, I loved Wonderbread. Seems odd now…I think it tastes like paste. Then again, I liked paste when I was a kid, too.

Paste and Wonderbread…not really much flavor there. White, bland, lacking in nuance.

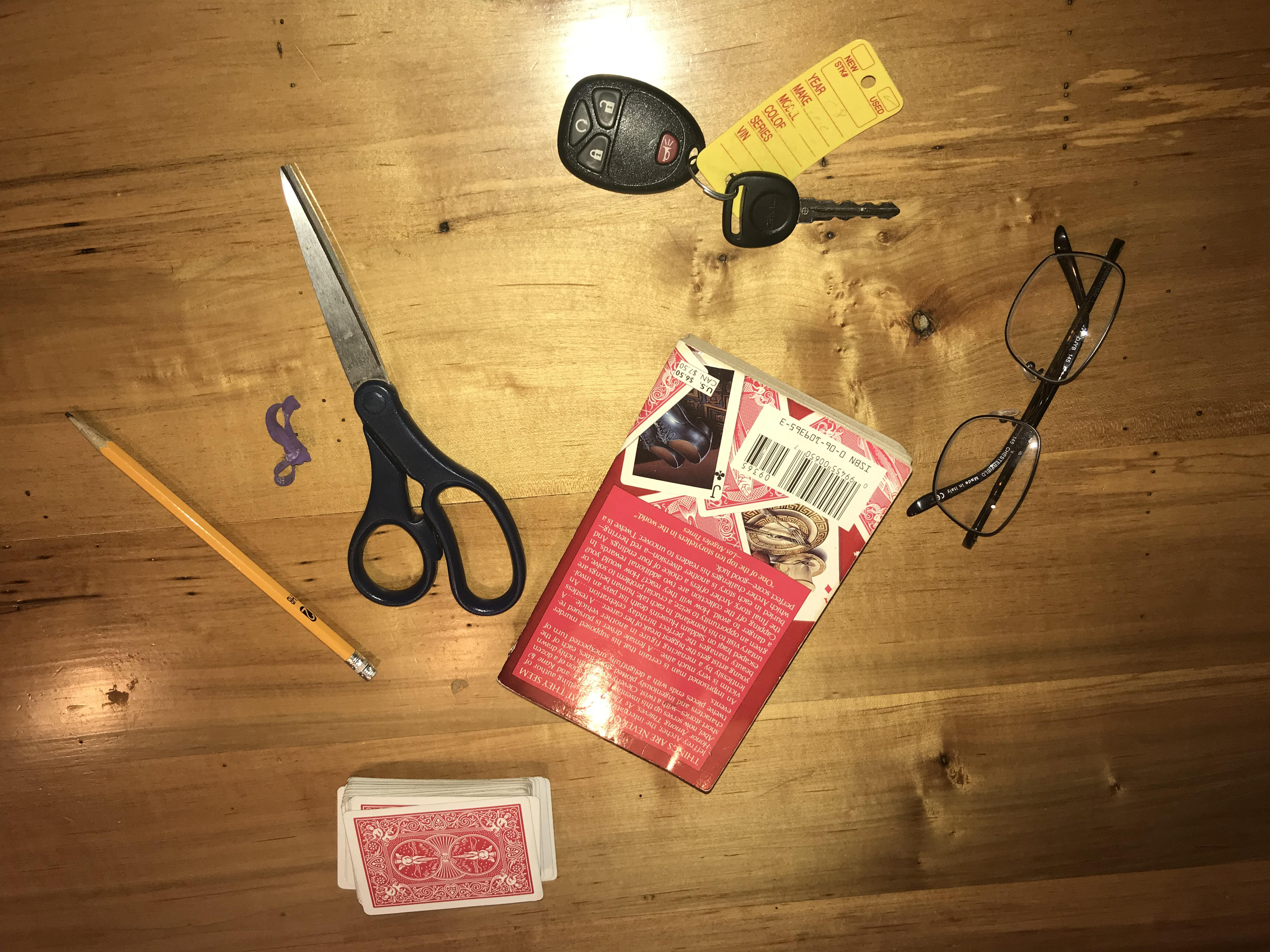

Unlike Shakespeare. The complexities of language stimulate the eyes, the ears, and the heart. Like Tim O’Brien says in The Things They Carried, you can feel a true war story with the stomach.

However, without sophisticated language skills, it is impossible to truly experience the full effect of Shakespeare. It takes a developed palate to appreciate artisan whole grain bread, so we must help students develop an appetite for dense language.

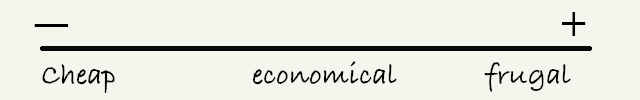

I begin teaching the concept of connotation by drawing a line on the board. I explain that the line represents a continuum of negative feelings, or connotation, on the left and positive feelings on the right. Then, right in the middle, I write the word “economical.” Then pick a random student and make up a story.

“We all know that Chad has been working a lot lately. He’s been saving up for a new truck. Been doing pretty well, too, banked a couple hundred dollars last week. But, he just started dating this girl, and it’s her birthday, so he has to choose: money for his truck or for a birthday present? He needs a truck to get to work, but he really likes this girl.

Let’s say we like Chad, and respect his choice to spend $8 on some flowers from the grocery store. What word would best describe his financial choice? Frugal? Yes, that means responsible with money. Now let’s pretend that we’re jealous. We like the girl and would spend more money to really demonstrate our affections. How would we describe Chad then? Cheap? A Tightwad? Absolutely.

See how the three words mean essentially the same: conservative with money. However, they carry different emotional meanings, or connotations, which reveal tone…how the writer or speaker feels. ‘Frugal’ shows that we respect Chad. ‘Cheap’ reveals that we despise him. ”

That’s my introduction. I will then reinforce the concept with another triad of similar words, skinny, thin, and slender, perhaps, or sluggish, slow, and leisurely.

Many times I will transition this lesson directly into one about similes and metaphors. I make the point to students that when invoking a comparison, a writer invokes the emotional value of that object. For example, the metaphor “Catherine is a ray of sunshine in her father’s life” conjures the positive aspects of sunshine: warmth and brightness. Or, on the other hand, the indirect metaphor, “Catherine slithered into the room” invokes the negative connotations of a snake: deceitful, venomous, and evil.

Once students understand how specific word choices reveal tone, we can begin exploring how Shakespeare employs this concept. I find that, at first, when many students read Shakespeare I feel like I’m eating Wonderbread again. There’s hardly any inflection, little emotion, and, even in a performance setting, no facial expression or body language. In these situations, students have not had an opportunity to connect with the text.

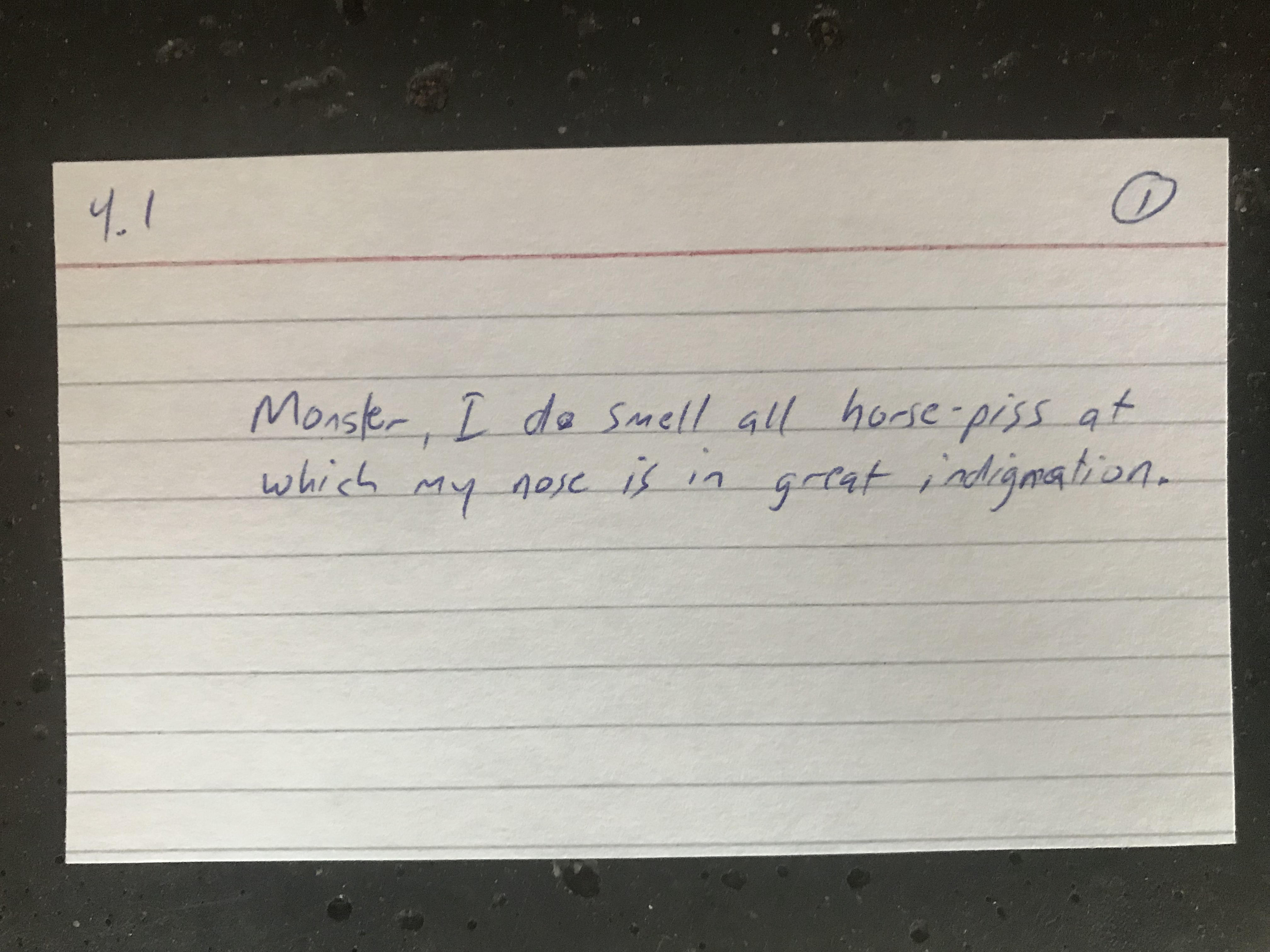

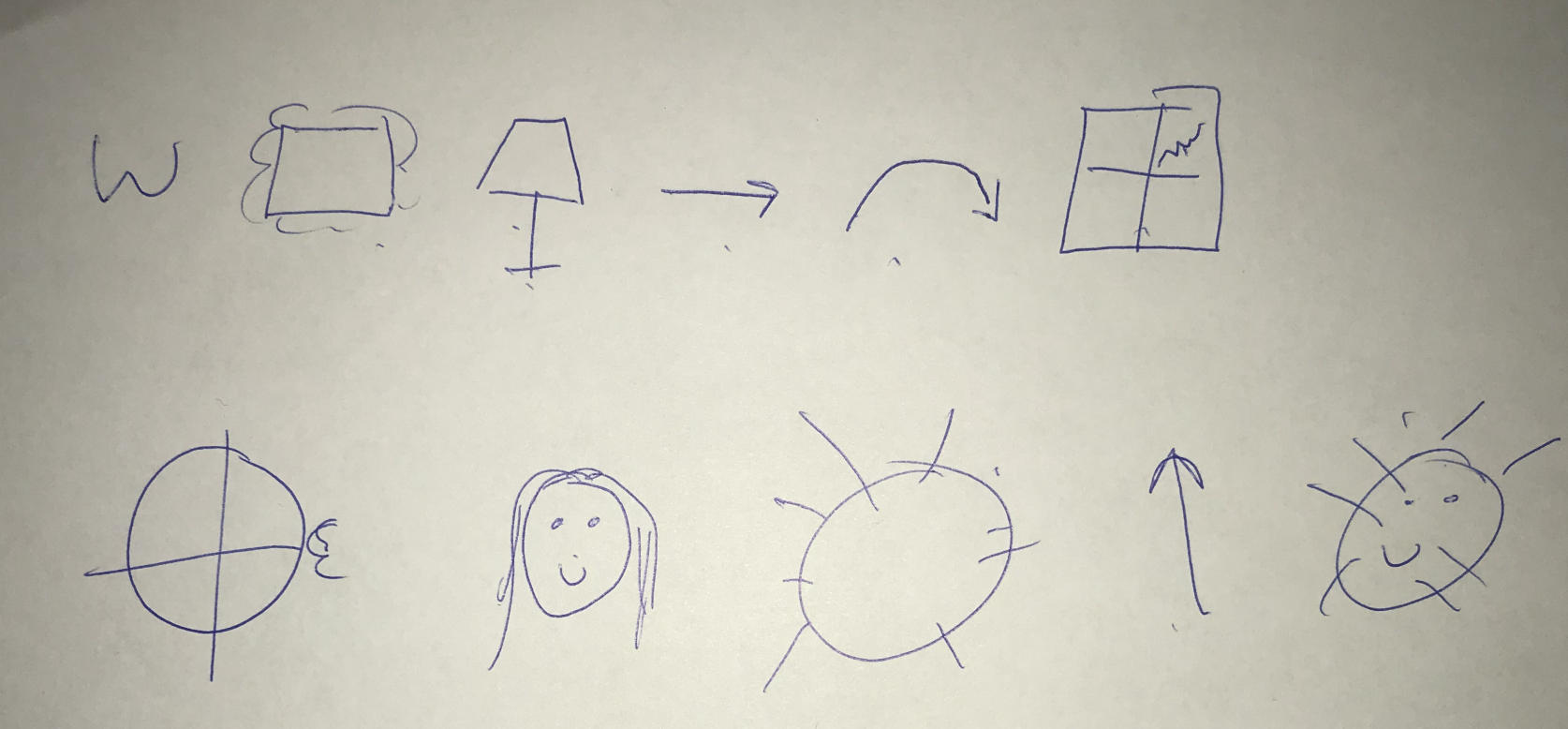

This process, however, provides a chance to relate the language to their memories and prior knowledge. It’s based on this activity from Shakespeare and Company called “Dropping In.” However, I use a variation that, quite frankly, I can’t remember how much came from the workshop that I attended, additional reading, or adaptation over time. But anyway, it goes like this:

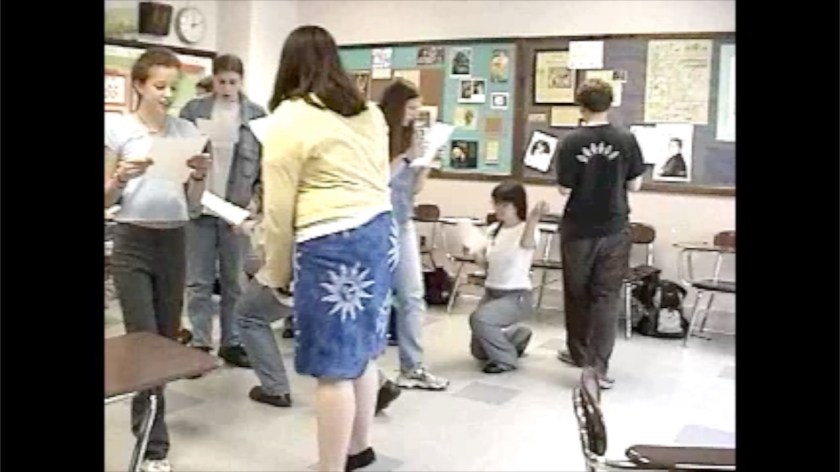

I put students in groups of four and give them a section of text that contains connotation laden language. I ask them to read through the passage and make a list of the powerful words. After each group has selected their words, I model the following process then ask each group to continue on their own.

Each student takes a turn in the “hot-seat.” They don’t have to do anything but think and point. The group chooses a word from the list on which to focus. Then they take turns asking the hot-seat student a question about that word. When they formulate a question, they raise their hand. When the hot-seat student points at them, they may ask the question. The hot-seat students don’t answer, they simply think about their response. During that time, the other group members think of other questions and raise their hands. It is important that group members raise their hands. If they blurt out questions before the hot-seat student has had an opportunity to process the previous question, then the opportunity to “form bonds” with that word has been lost.

Let’s consider, for example, the word “rage.” I might ask:

When’s the last time you felt rage?

Have you ever caused someone else to feel rage?

Does rage build slowly or come in a flash?

Where in the body does rage live?

If one particular animal symbolized rage, what would it be?

If you wanted to communicate rage with a musical instrument, which one would

you use?

I tell students to ask as many questions as they can. When they begin running out of questions, move on to the next word. If I have an actor working on a particular speech, I leave that person in the hot-seat. If we are doing classwork, I rotate each group member through the hot-seat with each new word. I find that although being in the hot-seat intensifies the experience, all group members receive the benefit of internalizing the questions.

After the groups have covered their list of words, or after a set amount of time, whichever best meets the needs of the lesson or class, I have each student stand with a copy of the text, and recite the passage, out loud, to the wall. (Or, if I’m in the theater I have them perform it out to “the space.” If I have them face the middle of the room they become distracted looking at each other and do not fully engage with the text.) Then we discuss as a class, “how did you find reading the passage at the end as opposed to the beginning?” Inevitably, students say that not only did the passage make more sense but it also seemed to resonate much more…they were better able to see and feel the images.

One of my most powerful experiences with this activity came from working with MaryAnne. As a student, she struggled with the decoding of text but performed well once she embedded the language into her head. She was working on a monologue from Comedy of Errors. She had picked out her list of words and several of her cast mates and I sat on the stage asking her questions.

After we had finished, she stood up and performed the monologue for us. The words seemed to resonate from somewhere deep. They carried tone, color, and nuance. We could hear and see the connotation of all the power words. And she, too, seemed to be carried off somewhere. When she finished, she just stood there. We just sat there, not just rapt in the performance but aware that we were witnessing someone fully experiencing Shakespeare. I remember her shaking her head, blinking her eyes several times and saying, “the words…the words.” I truly believe that she had, in some manner, hypnotized herself with the language.

On the other end of the spectrum, I find that some classes need me to help them maintain an academic environment. There’s a fine line between having fun with some silly questions and not taking the activity seriously Other students may need help them come up with questions. , so be prepared to help focus some groups and help create questions. Perhaps even a reference sheet with questions like “When was the last time you felt______?” “What’s your strongest memory of__________?” would be useful for struggling students.

So much of the artistry in Shakespeare comes from his word choices. His working vocabulary of 50,000 words, however, often overwhelms students with developing verbal palates. Teach them to chew, however, and really savor the subtle flavors of each morsel, and they will never go back to Wonderbread.