You have reviewed puns, shown examples, and discussed why they’re funny. Activate Prior Knowledge? Check! You begin the opening scene to Romeo and Juliet and model raucous laughter at the appropriate (and inappropriate) parts. And yet the students still look at you like you’ve sniffed too much glue. Then you realize…they’re right. These old references just aren’t that funny to modern audiences. Throw a couple of pool noodles into the mix, however, and you can transform archaic language into uproarious comedy.

More Matter, Less Art…

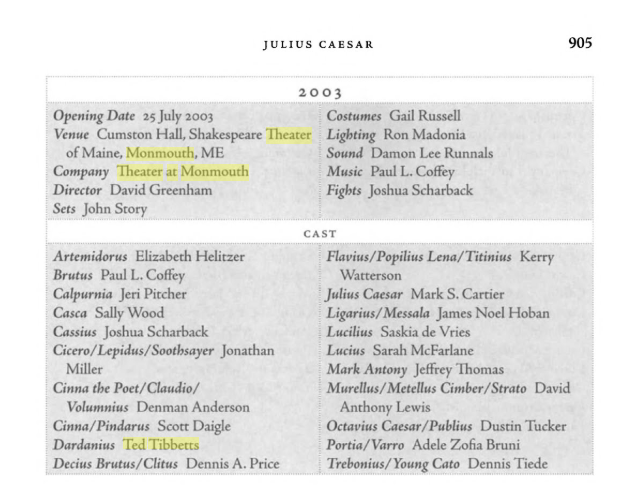

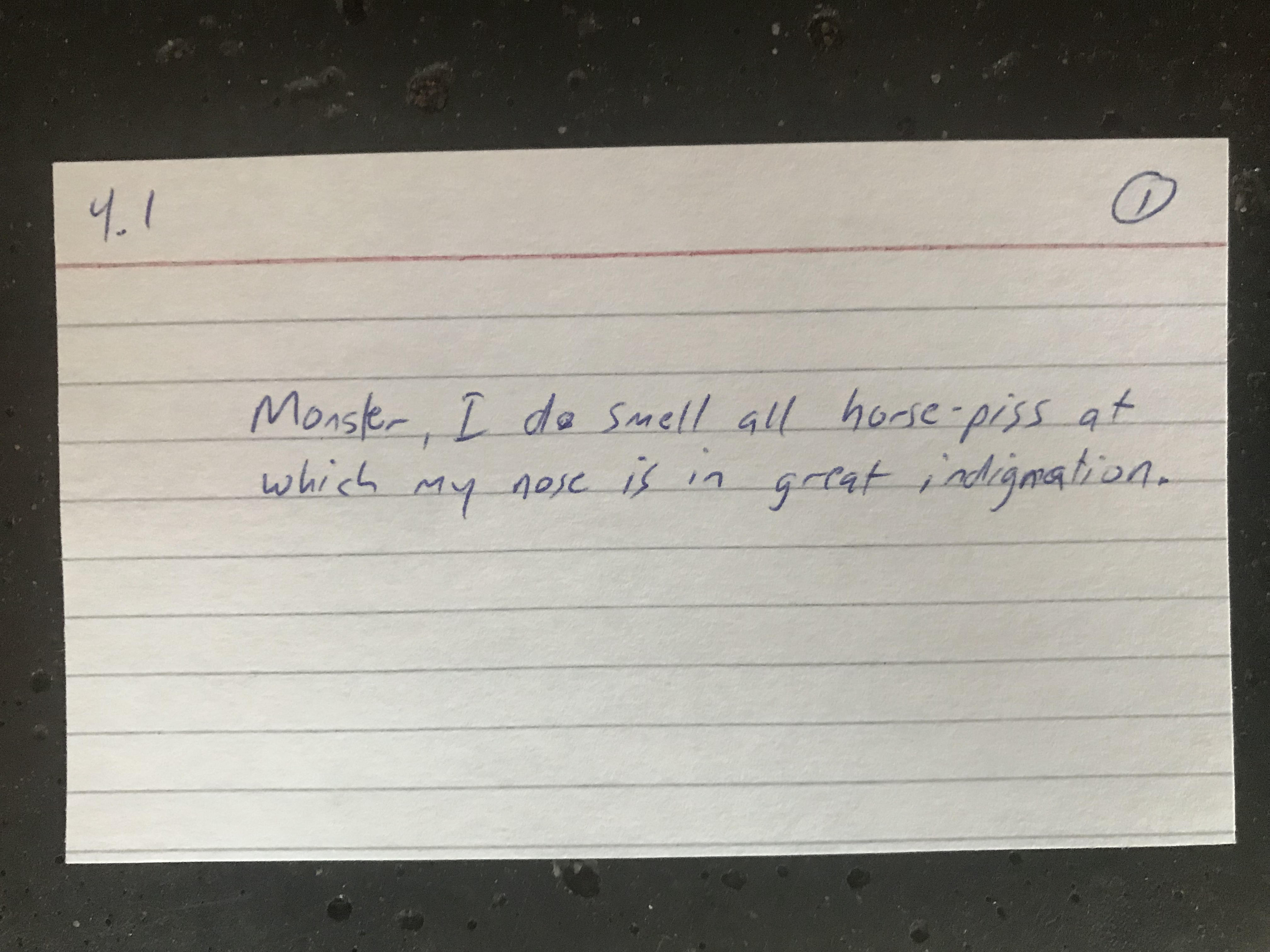

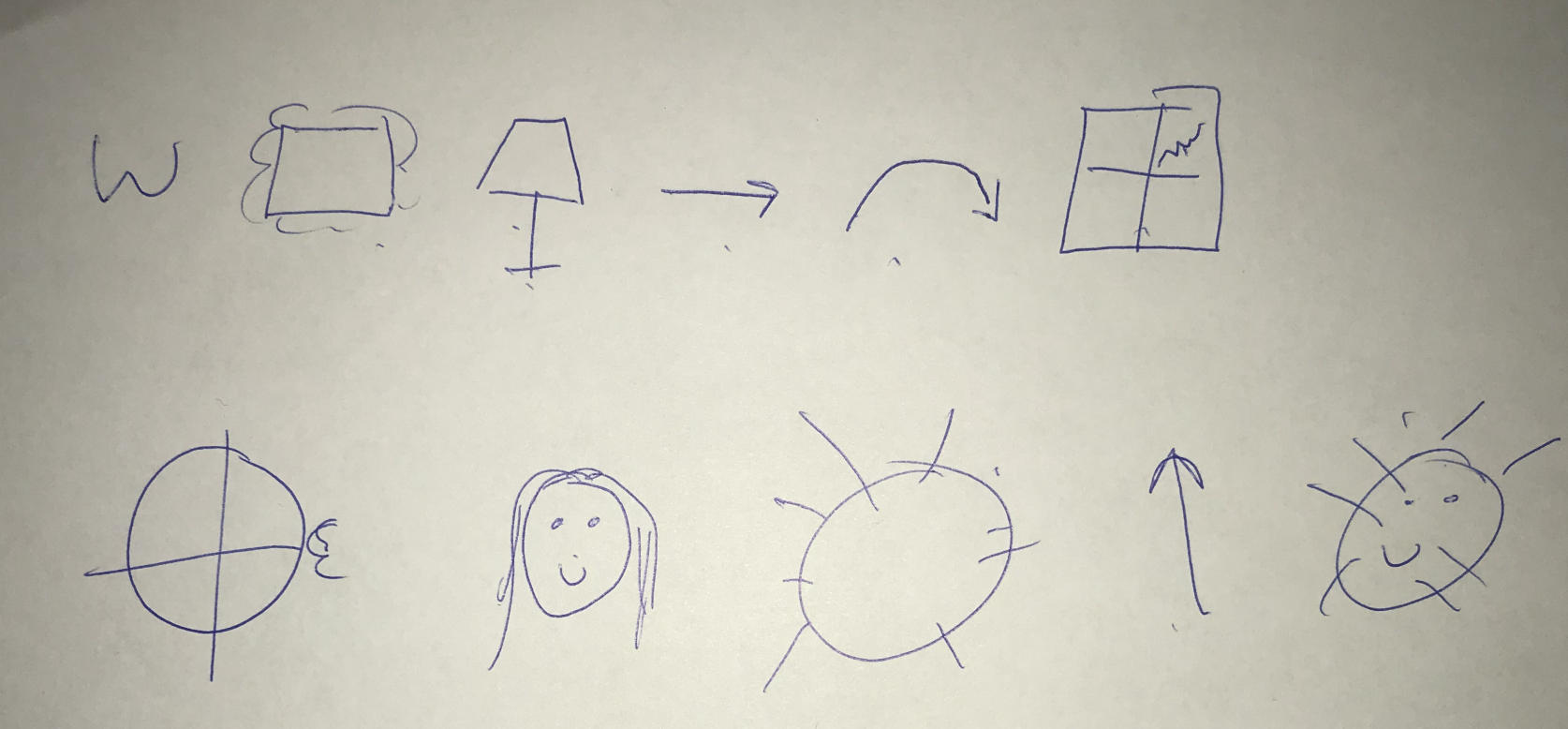

After you’ve done your due diligence by explaining puns, hand out a copy of the Sampson and Gregory in Act 1 Scene 1. (You can download a blank copy here, and a completed one here.) Tell students to look for similar-looking words that could indicate a pun. They should then circle the punning word and draw an arrow back to the word it puns against. For example:

I model the first three lines with class; then students work through the rest of the passage with a partner. After they have identified the puns, we complete a little formative assessment and review their choices. “Back in the day,” as my students love to say, I used this almost-as-archaic-as-the-puns-themselves device known as an overhead projector. Using a dry erase marker to draw circles and arrows (“And a paragraph on the back explaining what each one was to be used as evidence against us!” Sorry…couldn’t resist.) I explained each line. These days, I usually project my screen and simply highlight the puns as students follow along and make adjustments as necessary. With a tablet, I’m sure you could upload the text and then use a drawing app as a visual reference for students.

Before getting too deep into this activity, I also consider my audience. The puns at line 20 become sexual as Sampson and Gregory take bawdy stabs at each other. Gregory, with stereotypical male swagger, claims that he will “cut off the heads of the maids…Take it in what sense thou wilt.” Sampson, belittling Gregory’s male equipage, responds, “They must take it in sense that feel it.” Not to be put down, Sampson maintains that “me they shall feel when I am able to stand.”

It is up to the teacher’s style, community attitude, and student maturity how, or if to deal with this subject matter. When I workshop this scene with middle schoolers, I cut this part out. Most of my high school students get the jokes themselves when I simply explain that these jokes refer to virginity and “the apparent state and size of a part of male anatomy.” Attention is usually rapt at this point.

Suit the Action to the Word

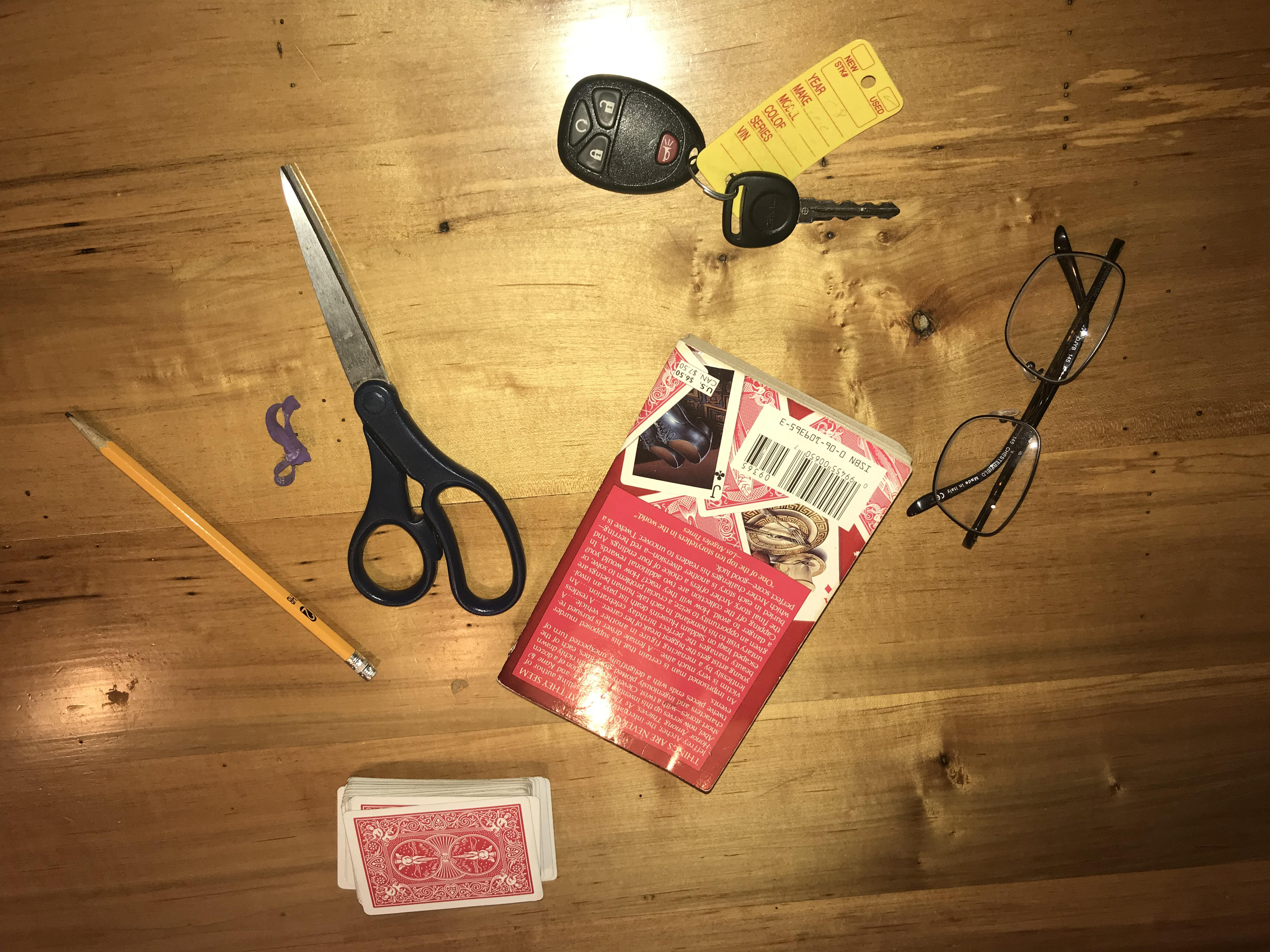

Then I pull out the nerf noodles. Waving them around usually ensures a rapid and enthusiastic mustering of willing participants. I choose two students to read and tell the rest of the class that they must help act it out. I give the readers the noodles and tell them that whenever they come to a circled word that has an arrow pointed back to the other character’s word, they get to whack them with the noodle The only two places they can hit them, though, are the shoulder and the hip. (With some high school boys, especially, we’d have to begin concussion protocol if they were allowed to hit each other in the head!) Also, I remind them that they are friends and not enemies. This is a verbal joust for fun, not mortal combat. (That comes later!)

In order to emphasize the playfulness of the text, I set the scene. I tell students to imagine that they have just finished lunch and are hanging around waiting until it’s time to go back to class or work. Sampson and Gregory have started talking and making jokes at each other. At each palpable hit, the audience students must laugh uproariously, even if it isn’t overly funny. This helps set up not only the mood of the scene but also provides something for Sampson and Gregory to play off. Furthermore, their participation invites engagement from everyone and not just the readers.

Then off we go! Sometimes I have to encourage more reticent students to increase the enthusiasm of their laughing, but suddenly, dull, boring and archaic language becomes engaging. Many times, too, Sampson and Gregory start playing to the audience, pausing for dramatic effect, and taking bows. The energy from the audience pushes them to a point where they can simply react as opposed to worry about how to act.

Then we get to the brawl, but that’s a subject for another post….

Our Revels Are Now Ended

After completing the scene I like to discuss its impact. How did students like the activity? What mood did the scene generate? Why does Shakespeare open the play like this? Students often present insightful ideas here and debriefing the experience often solidifies the idea that “Hey, this Shakespeare unit might be fun after all!”

Although I love opening Romeo and Juliet with this activity, it can be effective for other Shakespearean word-play situations as well. For example, I often use it for Beatrice and Benedick, in Much Ado, Falstaff in and Hal in Henry IV Part 1, Lorenzo and Lancelot Gobbo in Merchant of Venice or Feste in Twelfth Night. I love it because of its balance. The close textual reading requires students to really grapple with sophisticated language, however, they discover the rewards in a fun, engaging, visceral and visual experience to truly solidify their learning.

So break out those pool noodles! By beginning the Romeo and Juliet unit with a “15 Minute” play activity, then further engage them with the wordplay of this scene, your students will come to class the next day and excitedly ask, “Are we doing Shakespeare today?”