Teachers may often feel that their students’ attention span wouldn’t “clog the foot of a flea.” However, survey results from Prezi suggest they attention spans are not shrinking but evolving. According to this study, people’s attention “can be captured for long periods of time…, “ however, it must be “with compelling content that includes great stories and interesting, gripping visuals.”

Consequently, long Shakespeare passages can present challenges in the classroom. The compelling content may tell great stories, but unless the teacher has fostered the students’ ability to create their own mental “gripping visuals,” the only visuals students will see live inside their eyelids.

You could assign longer passages for homework with some sort of analysis or questions, but I wouldn’t exactly call it an interactive or dynamic activity. Plus it doesn’t address the issue of making it visual. More importantly, experiencing these great stories with the heart and the body make learning Shakespeare more powerful and more memorable.

So how do we teach it? One student reading and others listening? Small group discussions? Whole class discussion? These approaches still don’t create “interesting, gripping visuals.”

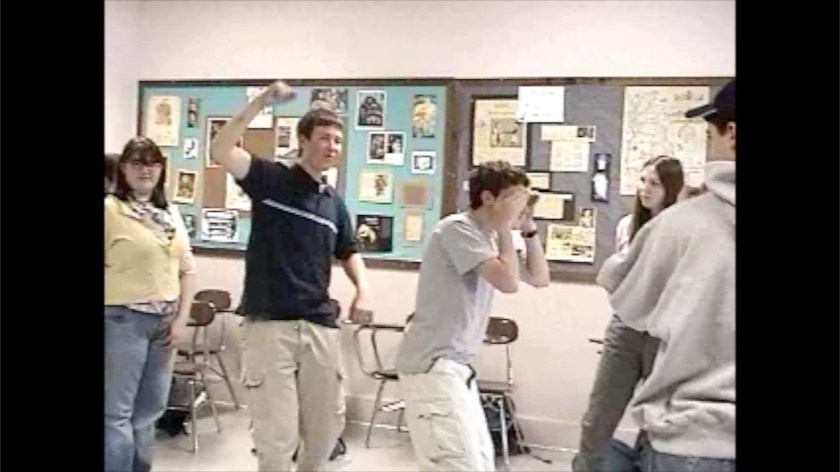

This activity captures the text, involves many participants, and creates memorable visual stimuli that not only fosters emotional response but also anchors ideas in memory. I call it “Monologue Puppeteer” because the teacher serves as the puppeteer directing students to act out the images of the passage. I often approach this activity in one of two ways.

Let’s say, for example, you’re teaching The Tempest and need to cover Prospero’s 17 ½ hour speech. (Shakespeare knew it was so long that he kept Prospero saying to Miranda, “Dost thou attend me?”) Here, the speech functions as exposition. Prospero and Miranda don’t need to experience the images. Prospero has already lived them, so he just needs to communicate information to Miranda. Thus, I have two students read these parts. (I make sure that I choose a fluid reader for Prospero!) As the students read the parts, I interrupt them and direct the other students in the class to act out the narrative. When Prospero tells Miranda “My brother…I loved and to him put / the manage of my estate” I tell another student, “go be the brother and manage his estate…whatever that means to you.” Then that student gets up and does some managy things. (He may need some encouragement and suggestion at first, but students get better at it.) Then as Prospero describes how Antonio can “grant suits” and awaken “an evil nature,” I direct the student playing Antonio to act out these images. Then add in an Alonso and Gonzalo, all miming parts read by Prospero. I usually add students to be the younger Prospero and Miranda, the boat, the library, garments and linens to get more people involved. By hearing, seeing, acting the images, the language becomes more memorable.

Other times, I want to emphasize the emotional impact. For example, in Juliet’s “My dismal scene I needs must act alone” speech, she contemplates the possibilities of drinking the potion. In order for her to focus on the experience instead of the written text, I have her stand. And another student, standing behind her, reads the part. As this student reads, I direct other students to act out the images. Juliet can watch the dagger, “lie thou there,” feel the “faint cold fear” that thrills along her bones, smell the “loathsome smells,” (It’s always fun to tell a student, “go be a loathsome smell.”) and hear the “shrieks like mandrakes.” The student playing Juliet inevitably feels claustrophobic by the end of the monologue. Even more uncanny, EVERY time I’ve done this activity with a group, I can point to any student and say, “what was he or she?” and the rest of the class can tell me exactly what image they portrayed. Even coming back to class two days later I can ask, “What did Juliet imagine before she drank the potion?” and recall nears 100 percent.

This activity can also be an engaging way to introduce Shakespeare plays. I always begin a unit by assigning parts, reading a summary and guiding students through the entire plot. Doing this before we begin helps them from becoming lost in the storyline as we progress through the unit. I omit servants and minor characters to simplify the plot but direct students to be the boat that sinks or the bush that Romeo hides behind to create more visual images and increase engagement. I also use it to review tricky parts of non-Shakespearean texts. Acting out the Boo Radley, Bob Ewell, Jem and Scout fracas under the oak tree clarifies the confusion about who had what knife.

Engagement has emerged as a new buzzword in education over the last few years, and with good reason. It facilitates learning. And as our attention spans change, these strategies increase that engagement and create “interesting, gripping visuals” that provide opportunities for students get out of their seats and experience Shakespeare (and other texts!) visually, emotionally, and kinesthetically.