-Ted Tibbetts

Memorization has become a lost art. Proof? Recite four phone numbers from memory. If you can do it, you’re better than me! With immediate hand-held access to information, we seldom need to learn anything by heart. However, situations occasionally arrive when we wish we had the brain power to commit things to memory. These seven strategies will help!

1. Read and Repeat

In this method, you read the words, then repeat them to yourself over and over. This traditional method has stood the test of time for a reason: it works. Kind of. The big challenge comes with maintaining engagement. Often we think we are repeating the words in our head but, rather, we think about what’s for dinner thereby negating the process of lodging these words into long-term memory. Instead, we’ve just wasted 20 minutes. This approach can be effective, however.

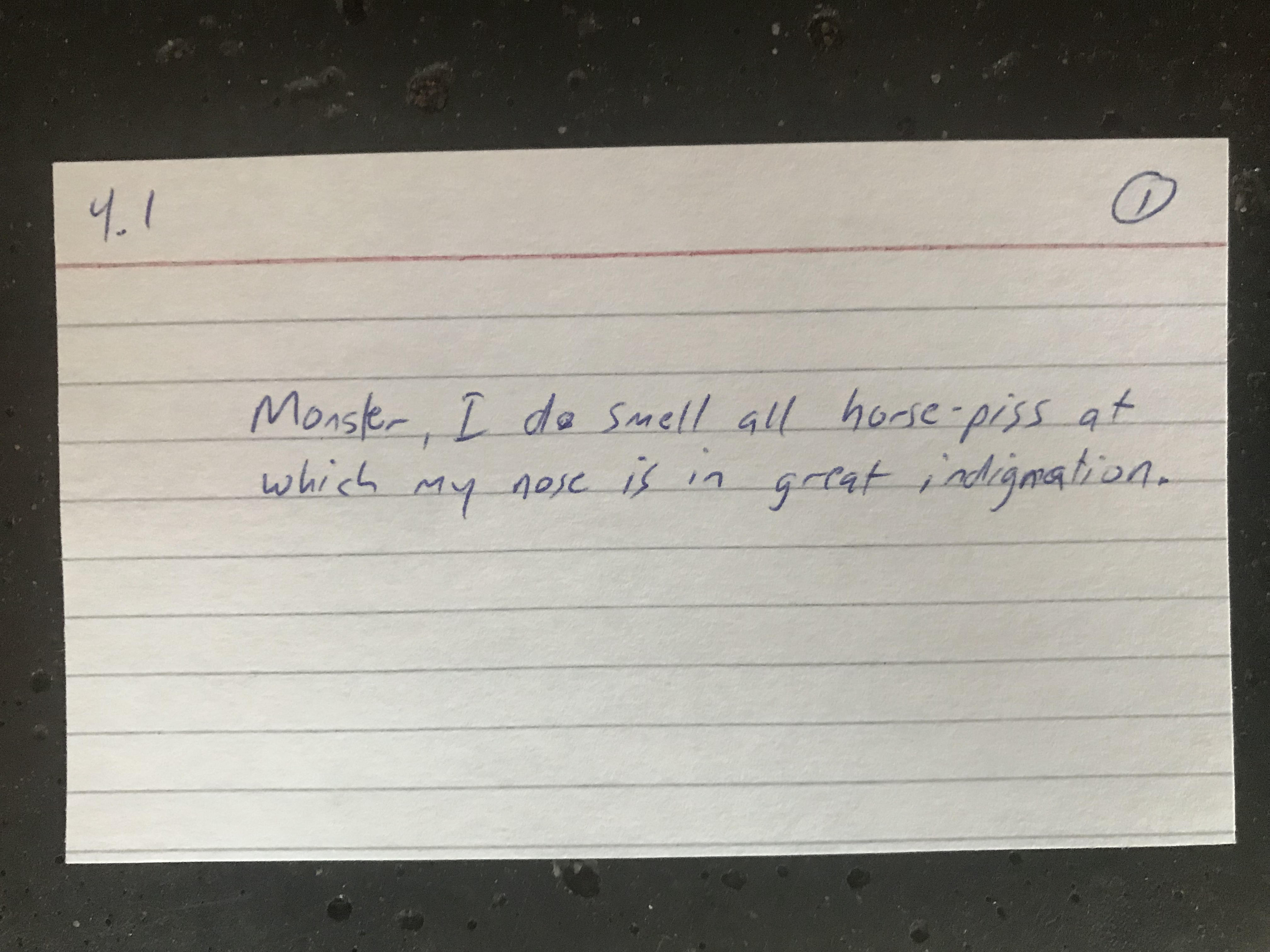

Consider adding the following steps. Write cue lines on one side of an index card, then write your lines that come after on the other side. Maintain line integrity: in other words, begin a new line on the card as it shows on the script. This will help to parse the text appropriately. In addition, write the act and scene in the top left of the card, and number the lines in order in the top right. This will help reorganize them when you inevitably drop them on the floor.

Carry a few cards around with you over the course of the day. Set goals for yourself like, “I’m going to learn these two cards by the end of the day.” Then, whenever you have a quick moment, pull them out and rehearse the lines. Spending 30 seconds ten times a day will be far more effective than spending five minutes all at once. Moreover, you can capitalize on those “dead” times like when you are waiting in line or walking from one place to another.

2. Record and Listen

With the ubiquity of earbuds these days and the proliferation of podcasts, auditory channels can be a highly effective way to transfer information. Record your lines with a voice recorder app, then play them back on your phone. You’ve just created your own line podcast!

3. One Word at a Time

This approach can be tedious but highly effective for those slippery lines that just don’t seem to stick. Part of its effectiveness comes from the repetitions you get from the recall. It’s like those times where you say, “I know it, it’s on the tip of my tongue” but you have to mentally grope for the thought. It’s lodged in your brain somewhere, but you’ve only created one neural pathway to retrieve that bit of information and your brain says, “Now where did I put that file?” In this technique, you exponentially increase the number of recall repetitions. For example, say you want to memorize Hamlet’s line “I have of late, but wherefore I know not, lost all my mirth.” You would say, “I…I have…I have of…I have of late…I have of late but” and so on, until you have committed that line to memory. Be sure to deliberately look away from the page so you know you aren’t merely reading the line. As I said, it takes time and is tedious. Thus, I save its use for those awkward lines with which I struggle.

4. Backward Line Recall

Like the One Word at a Time technique, this strategy can also be tedious and also incredibly challenging. But, it is an outstanding way to firmly anchor text in memory and smooth out lines plagued by a slow recall. Review the line on which you want to focus, then try to say it backward. For example, Macbeth’s line would be, “nothing signifying fury and sound of full idiot an by told tale a is it.” Forcing the brain to grasp the relationships between the words strengthen and deepen the neural connections and make recall much smoother and faster.

5. Pictographs

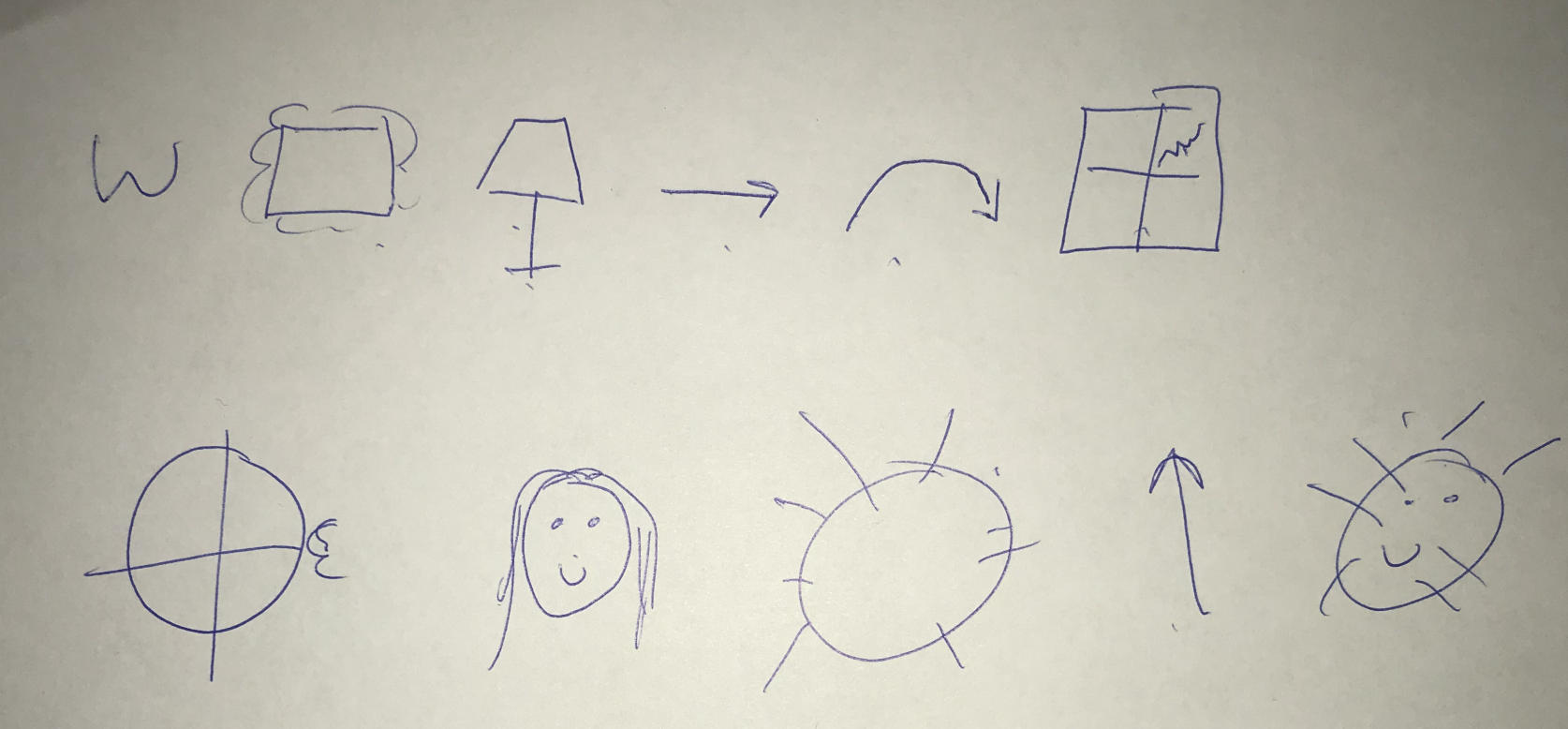

This method may be the most powerful because it works on several levels. Draw a quick picture or symbol that represents most of the words of the line. (I usually skip articles and prepositions) This is not fine art and does not have to be a direct representation of the word, just something that you associate with the word. For example, for Romeo’s line, “But soft, what light through yonder window breaks, it is the East and Juliet is the sun,” I would draw, well, a butt, then a pillow, (because it’s soft), then a lamp, then a straight arrow to represent “through” then an arc arrow to represent “yonder,” then a window, then a crack in the window for “breaks.” A compass for “East,” a face with long hair for “Juliet,” and then a sun. You should do this quickly for time’s sake and not agonize over getting the perfect image. You just want to connect an image with a word. By doing so, you are creating additional neural connections since the brain processes images differently than words. In addition, unlike the Read and Repeat, there is no way to mentally check out of this exercise…you have to stay engaged.

6. Objects

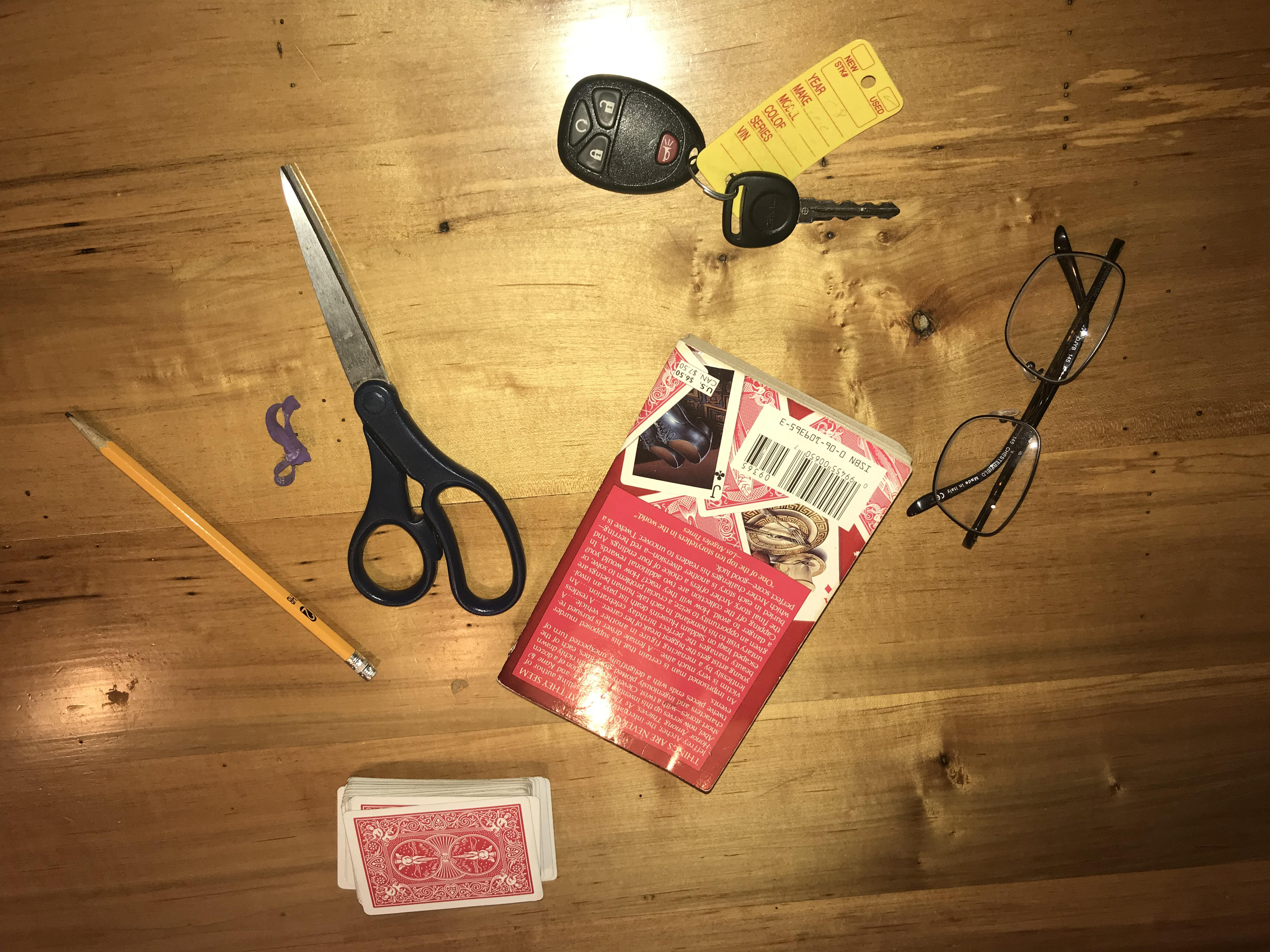

Like pictograms, using objects highly engages different parts of the brain and also the body for those kinesthetic learners. Assemble a pile of about a dozen different random objects: keys, a cell phone, a pencil, chapstick, a coin, some scissors, a roll of tape, a hat, a shoe, some glasses, a tack, and a book for example. Then assign the object to a word in the line that you want to memorize and “animate” it as you say the word. Say, for example, you want to learn Marc Antony’s line: “I come to bury Caesar not to praise him.” I would say something like, “Okay, ‘I’…well, glasses go over the eyes, so the glasses are “I.” And, “come”…well, I need keys to drive to come home. Then “‘to bury.’ Well, I’ve been buried with reading lately so the book will be that. Then ‘Caesar.’ He was stabbed…so scissors will be Caesar. And so on, until each significant word has an object attached to it. Then, say the line while picking up the associated object. Once you have the line down, begin picking up the objects in random order and saying the word until the line becomes smooth.

7. Weird Places

Once you have the lines mostly memorized, try changing your location. If you only memorize in one place, when you get into a different environment you are more likely to forget what you learned. (Don’t ask me how I know that.) This strategy also enhances engagement. By this time the brain feels like it’s at a faculty meeting so it tends to check out. By putting yourself in a weird place, however, suddenly memorization seems fresh again. Lie under the kitchen table, stand on top of the dryer, sit in the back of the closet, yell lines at the ocean. Not only will it feel quirky and new but your brain will also acclimate to multiple locales. When you get to the performance, your brain will think, “This isn’t as weird as dangling upside down from the monkey bars.”

A few last bits of advice: set a schedule and adhere to it. I usually have to memorize something three times before it truly sticks. I think I have it, then the next day it’s gone. I learn it again, then it’s gone. By the third time, though, it becomes much more firmly entrenched in long-term memory. Knowing that I budget “forget time.” And, to reiterate, I have found that multiple blocks of short time work much better than fewer blocks of longer time. So have at it and let me know how it goes!

Check out video post here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ijapTY5-nfE