Students often struggle to get beyond themselves while acting Shakespeare. And understandably so. Wrestling with complex language in front of a jury of their peers can raise anxiety levels. By emphasizing “playing” with the language and the themes, however, teachers can help students find the relevance in the text, the meanings of the words, and the power of Shakespeare.

Early in my teaching career, I was fortunate to have several of my students participate in a summer Shakespeare program. I found the director at the time, Henry Wishcamper, a genius at connecting adolescents with Shakespearean text. He had an uncanny knack for making the situations relevant to them by invoking their imaginations and feelings when performing. So not only did I pop into summer rehearsals from time to time to watch him work, but when I directed my own Shakespearean acting troupe, I often invited him to workshop with my students. I learned as much as them.

One fall we were all learning a monologue, so I invited Henry to workshop with us. One student was working on Benedick’s “I do much wonder that one man, seeing how much another man is a fool” speech from Much Ado. Henry took several minutes to construct a mini-man-cave set out of a couch, and table then built a mock TV with a stack of books.

“Okay,” he said to the student. “The big game is on. You’ve been excited all week for it because your buddy Claudio has been planning on coming over to watch it. You made wings, you’ve got chips. And he just called and ditched you because he needs to go to the mall with his girlfriend.”

He continued to coach the student through the scene by having him start on the couch, (“Here, pretend this cell phone is the remote.”) then work himself up into a rant pacing around the room. Then, what if you saw a commercial on TV with a girl in it? Maybe that sparks the ideas of “Rich she shall be that’s certain.”

Suddenly, the text didn’t seem so abstract. It has context. And energy.

This technique works really well for what I call the Aubade scene in Romeo and Juliet. Romeo must leave Juliet’s room before dawn lest authorities (or, more frighteningly, Juliet’s mother) catch him violating the terms of banishment. Of course, neither of the two want to be separated, but the Nurse bringing news that “Your lady mother is coming to your chamber,” certainly raises the stakes.

I usually scatter several “incriminating objects” around the performance space: a love letter, a belt, a picture of Romeo, (you can get really creative here). Then I tell Juliet, “Okay, mom’s coming, you’ve got to clean this stuff up without getting caught.” Now there’s a sense of urgency! Sometimes, if I have students that would respond well, I set up a game. I tell the student playing Lady Capulet, outside the room, that “you suspect SOMETHING, just not exactly sure what. Be looking for something incriminating. If you find it, you get to make Juliet sing an embarrassing song in front of the class.” Then I come in and tell Juliet, “Your mother’s coming. If she discovers that Romeo was here you have to sing an embarrassing song in front of the class, If you get away with it, SHE has to sing the song.”

This often creates hilarious improvisation. I’ll sometimes cheat and toss something on the floor at the last minute. Suddenly Juliet has to stand on it, distract her mother, then hide the object behind her back or stuff it into her pocket. Again, it creates energy for the actors and the class while providing opportunities for actors to find authentic stage business to bring the text to life.

When teaching Antony’s “I come to bury Ceasar not to praise him” speech I come to class armed with a paper recycling bin. I tell all the students to grab three or four pieces of paper, crumple them up, and prepare to throw them at Antony.

Then I tell Antony, “you’ve got a hostile crowd here. If you don’t win them over, well…they’ll probably kill you.” Then I tell the class, “when Antony first speaks, feel free to boo him. Throw paper at him. Not too much at once, you may want to save some ammo. However, when he makes a valid point, you’ve got to quiet down and give him his due. Go back and forth. He won’t win you over immediately, but will at the end. But make him work for it.”

And indeed, Antony now has to fight for his life under a barrage of paper missiles. But it’s dynamic. Shakespeare is now fun.

For students not quite ready to manage these complexities, however, you can set the scene more simply. For example, for the Friar Laurence/Friar John scene in Romeo and Juliet, I tell Friar John, “Go out, run down the hall, up the stairs, back down the stairs, back down the hall, then burst through the door and read your lines.” Of course, he brings news that he could not deliver news to Romeo.

His “Holy Franciscan friar! brother, ho!” line, always delivered authentically breathless, helps portray appropriate energy. In addition, while Friar John runs madly through the halls I usually provoke Friar Laurence.

“Where’s Friar John? He should have been back a long time ago. I wonder what’s going on. The message was pretty important. You know how Romeo is. What’s going to happen if he didn’t get the message. You’d better find out soon.” Meanwhile, he and the rest of the class sit there with tension building. Both for the plot and to see how Friar John responds to running two flights of stairs. (Much more interesting that quadratic formulas).

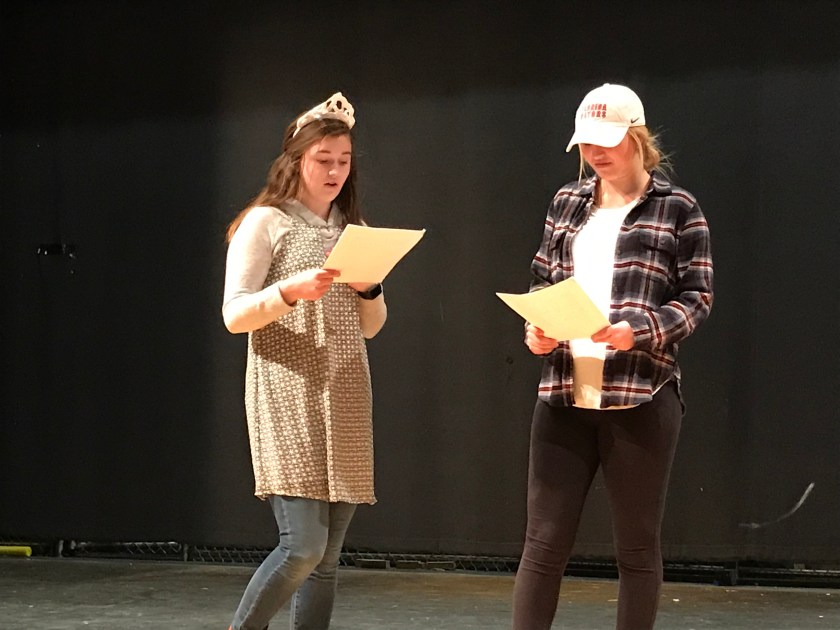

Many times, scenes aren’t as, well…dramatic. They serve as exposition or to move the plot along. Moreover, since when I teach Shakespeare in the classroom, much of our text work comes in the form of cold reading. Students have never seen the script before, so asking them to “perform” it with much alacrity would be unfair.

Thus, “setting the scene” in these situations usually entails explaining what will happen and often present some options of how the character may react. For example, in Twelfth Night, in the scene with Olivia and Viola I tell the students. “Orsino has been sending Olivia love letters for YEARS! Posting all over her social media accounts, (she would have blocked him but she’s too polite.) How do you think you’d feel, Olivia? Annoyed? Yes, for sure.

And you, Viola, you’re in a no-win situation. You love Orsino. If you achieve your mission you lose Orsino. If you fail, you’ve failed Orsino. But is your heart really in this? You’re right, probably not.

Okay, now, Olivia, at some point in this scene, you become REALLY interested in Viola. So Viola, how would you respond to this sudden interest especially since you are a woman disguised as a man who is in love with Orsino. A bit awkward, you say? Probably so. Okay, let’s run it and see what happens.

Then they act out the scene. I will often stop them and suggest different responses or actions then ask which ones they like better and why. I will often add a physical component as well like, “Here, grab Viola’s arm, put yours under hers and walk her to the door. Good! Viola, how did that make you feel? Class, what did that action say to you as the audience?” And, because this process takes time, I will often skip parts of the scene to focus on others.

And remember, our primary goal here is not to rehearse actions that would “work” in a formal theater production but simply to access points to the text. How can we help students learn Shakespeare not with only their brains but with their eyes, ears, hearts, and bodies?

These kinds of activities may represent my favorite parts of teaching Shakespeare. I like helping students make connections and see the relevance of Shakespeare–the old coot. I like seeing their creative interpretations and often hilarious actions that far surpass any directing choices that I could make. And I love watching students grow from a Shakespeare-is-too-hard-and-too-boring-I-can’t-do-it mentality to a this-is-cool-can-we-do-it-again? one. By getting out of our seats, running around, and throwing paper, we can still wrestle with rigorous texts but we can do it with more excitement.

One thought on “Let the Imagination Forces Work: Set the Scene for Teaching Shakespeare”