If you’ve never seen comedian John Branyan’s “Three Little Pigs” Shakespeare style, go watch it now. It’s hilarious. I’ll wait.

Still laughing? (I loved it so much I memorized it as a monologue.) But he’s right: Shakespeare used over 30,000 words in his writing. While researchers suggest that modern audiences use more than the 3000 words suggested by Branyan, many teachers can identify with his line “‘What light through yonder window…’ What? Does this come on a DVD?”

In order to convince students that Shakespeare can be fun, we must first show them that the language can be accessible. (Hey, a significant portion of Shakespeare’s original audience couldn’t even read!)

I use variations of the following activities to accomplish simple goals. First, I want to foster familiarity. In other words, provide enough repetitions in speaking and listening so that the language starts to hear and feel “normal.” Second, I want to build voice skills of accurately reproducing the phonetic sounds as well as the proper phrasing. And I want to do this in ways that engage all students.

The structure of the Language

Students are not used to reading text in verse format. Thus, the inevitable pauses they place at the end of every line, needed or not, distort the rhythm and parsing of meaning. To help them, I use an activity called “Text Surfing.”

I say a sentence containing a list separated by commas. Something like, “This weekend I’m going on a canoe trip so I need to remember my paddle, my PFD, my canoe, and my splash gear.” Then I ask the students: when I finished saying “paddle,” how did you know that I wasn’t done my list? After several smart-alecky answers, we get to the truth of that matter that my voice inflection stays high, whereas, after “splash gear,” my voice inflection goes down.

Then I write the sentence on the board and illustrate my rising inflection by making a swooping motion up with my hand at each comma. I direct the students to follow along with me.

After introducing the concept I break out the Shakespeare text. I tell students to read it while paying attention to the punctuation. At everything except a period or exclamation point, they should raise the inflection of their voice and, for emphasis, make the swooping motion with their hand. I will sometimes pair them up and have them switch at every complete sentence if I feel they need some social interaction. I have them read for five minutes or so, circulating around the room and reminding them to “keep swooping!”

I tell them not to worry about meaning at all. In fact, I don’t care if they “understand a single word!” I simply want them to pay attention to the phrasing.

I like this activity for its simplicity. Rather than overwhelming students with complex meanings early in the unit, I focus on building success and familiarity one phrase at a time.

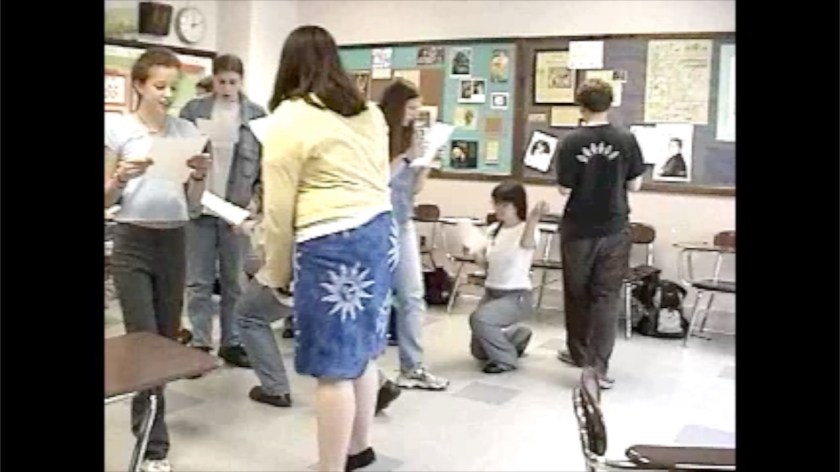

I call the second activity “Traveling Passage.” Similar to “Text Surfing” this activity focuses on the phrasing of the language. It adds, however, another layer of complexity. In addition, I like it because I can add movement. In this activity, I ask students to walk around the room while reading a selection of text. (Verse works better than prose.) When they come to a comma, change direction. When they come to a period, stop. When they come to an exclamation point, jump. When they come to a question mark, kneel. When they come to a semicolon or colon, shuffle their feet.

This can become a bit chaotic especially with a larger class in a small space. Embrace the chaos! The point is not to think about the theological ramifications of killing Claudius while he prays but rather to increase familiarity with the language and, hopefully, teach neophyte Shakespeareans not to stop at the end of every line. Understanding the nuances of meaning will come later!

Sometimes I find reducing Shakespeare to the ridiculous provides a wonderful catalyst for shattering student illusions that studying Shakespeare should be reverential and plodding. The language concept of inversion often contributes to this notion. Placing the subject and verb at the end of the sentence just sounds weird. Until you justify it by saying that Yoda does it all the time. For example, “When nine hundred years old you reach, look as good you will not.” If I have several Star Wars fans in class, I ask them to quote their favorite Yoda lines with inversion.

Then comes “Inversion Improv!” I ask for three students volunteers. I give them a situation like, “You’re on your way to a concert but got a flat tire,” and two minutes to improvise a scene where they introduce and solve the problem…while speaking in inversion the entire time. While it can be a challenge for some students, this activity has a huge upside: it’s funny, it’s dynamic and interactive, and it provides an opportunity to illustrate a component fo Shakespeare’s language and make it more understandable.

Language study does not have to be boring. In fact, it definitely shouldn’t be early in the unit. We can get more in-depth as we progress through the play. However, by using these hands-on, kinesthetic, and auditory activities, teachers can provide the scaffolding for more complex learning.