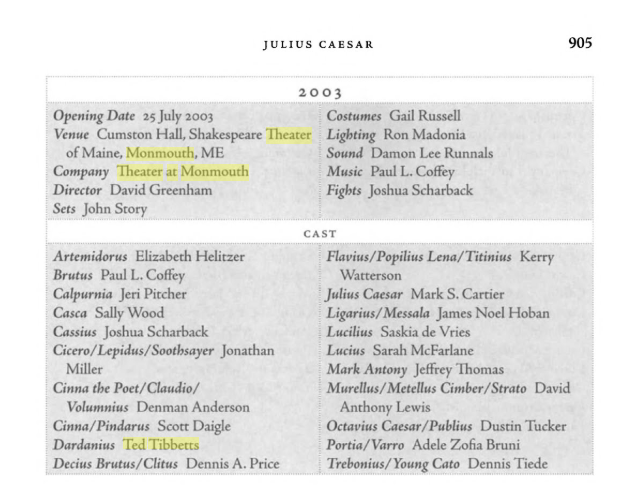

-Ted Tibbetts

We spend way too much time unpacking the language of rubrics. And, yes, I know, we want to make learning objectives clear for our students. And, yes, we want instruction, in some degree, to be data-driven. But when I think of the amount to time we spend sitting around in meetings trying to cram content into a digital receptacle and trying to pinpoint what we really mean by “sophisticated topic development,” I feel like a fly to the wanton gods. The most important learning can’t be measured in rubrics.

I was never an actor. In high school musicals, I played trombone in the pit band. In college, I played guitar and sang the songs with a lot of lyrics. (I was the only one who could remember all the words.) Throughout that time, however, I became more and more interested in Shakespeare. In graduate school, I TA’d for a Shakespeare class. Then I saw audition signs for Much Ado About Nothing. I figured if I truly was going to do this “Shakespeare Thing,” (whatever that was) I should experience it from the stage as well as the library. Besides, I was a musician and vocalist, how hard could a theater audition be?

I memorized, I practiced, I showed up…I forgot most of my lines. I fled to the comfort of the library (or was it the pub?) thinking my Shakespearean acting career was a tale told by an idiot. A week later I received a call from a grumpy and terse stage manager: “Do you want this part or not?”

“Part? What part?”

“You didn’t check the door?”

“What door?”

Various mumblings and expletives.

Anyway, I had garnered the part of George Seacoal. A brilliant casting, actually. The director awarded the educated but hopelessly inexperienced actor with a three-line part, who could actually be considered the hero of the play: he captures the villain. (Fun fact, by the way, the kid playing Claudio had been on the TV show Who’s the Boss with Tony Danza).

So, I thought, “This is good. I can learn Shakespeare theater with a small part and finish my homework during rehearsal.

I didn’t do ANY homework during rehearsal. But what I learned about Shakespearean theater affected teaching for the rest of my career. For years I had learned Shakespeare from an intellectual perspective, and, on occasion, from an audience’s perspective. However, the director facilitated activities in which students experienced the text with their hearts and bodies as well. And the rhythms, lines, language, and images continued to resonate in my head for hours after rehearsal.

When I began teaching Shakespeare in the classroom, I used similar strategies. While I didn’t have that director’s experience or theater knowledge, I did the best I could…and I attended workshops and conferences and researched theater techniques.

I also met the managing director of a local Shakespeare theater who visited my class once. I asked him if I could audition for a play. (I decided to leave out the details of my last audition.) He said, “no need, I’ve got a part all picked out for you.” So, I went on to add “Professional Shakespeare Actor” to my resume. Which really means they paid me $75 for the summer, that didn’t even cover gasoline expenses, to play various tiny roles…that I loved! I wasn’t in it for just the acting; I wanted to watch professionals prepare. I carried around a notebook, not for my own parts, but to ask the pros how they approached the text. I added these strategies to my teaching arsenal.

This approach made all the difference. Students showed up to school 15 minutes early to ask if they could work on their scenes. I started teaching a Shakespeare through Performance elective. Several students went off to a summer Shakespeare program. They went to the drama club, then came to me and said, “It was pretty cool, but it wasn’t Shakespeare. What if we had a separate club just dedicated to Shakespeare?” I thought, “Well, we’d probably have a dozen or so kids, why not?”

We ended up with around 25 students in the club, which turned out to be one of the most powerful student groups with which I’ve worked. In the fall we worked on skill development, ensemble building, and everyone learned a monologue (including me). In the winter, we cut a play to a 15-minute farce. In the spring we produced a full-length Shakespeare play and the first week of summer vacation we spend at the Royal Shakespeare Company workshopping with RSC actors during the day and attending the theater at night. It was truly an incredible experience. We completely took over a Bed and Breakfast in Stratford. One year I had the forethought to buy an extra ticket to the evening shows “just in case,” so I invited Bridget, the B&B owner to join us for the evening. “That would be lovely,” she said in her proper English accent. “I haven’t had a chance to get out to the theater all season. And” she added with a bit of a twinkle in her eye,” I know where the actors go after the show.”

So off to Comedy of Errors that night. Then to the Dirty Duck after the show to, hopefully, catch up with some of the actors. They came in alright, with their friends, and were immediately accosted by my students asking them to sign programs. Seeming a bit taken aback they politely acquiesced, then returned their attention to their peers.

For better or worse, American high school students are louder than British actors. Loud as they might have been, however, ignorant they were not. All had covered a Shakespeare play each year in English class. Most had taken the Shakespeare elective which covered four or five plays a semester, and in the club, we had referenced, workshopped or performed several more. So, forsooth, many of these students could speak knowledgeably about 15 or more plays. Enthusiastically they were connecting the Comedy of Errors to other plays, quoting various lines, talking about their favorite parts of the play and I could see the actors looking over with quizzical glances seeming to say: “Who the hell are these kids?” Within an hour the actors had ditched their friends and were hanging out with the students talking “shop.” (By the way, this can’t be assessed with a rubric. Can you imagine, though? “Can converse knowledgeably in a pub with an RSC actor about a line from Titus Andronicus…Exceeds the Standard!”)

I have continued to teach Shakespeare this way ever since. While I have changed schools and no longer direct a Shakespearean acting troupe, I still look forward to…okay, long for, those Shakespeare units. Admittedly, some of my more introverted students don’t look forward to it as much as me, but many do. And the growth that results from performing Shakespeare rivals any learning experience I witness in school. (To read my story about MaryAnn, click here!)

If someone like me, who forgot most of their lines in an audition, can use theater strategies to teach Shakespeare, anyone can! Give it a try, share the experience with your students, rethink the “Complete Works” and put the play back in Shakespeare!

.